By Oren Liebermann

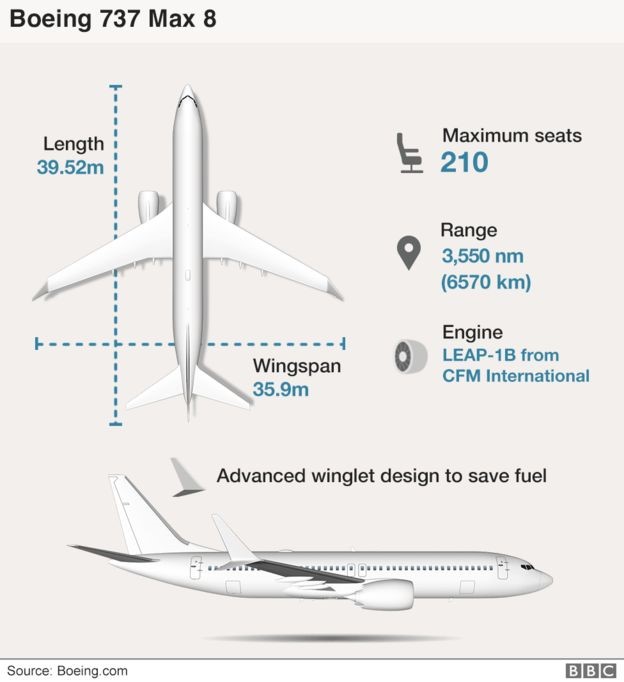

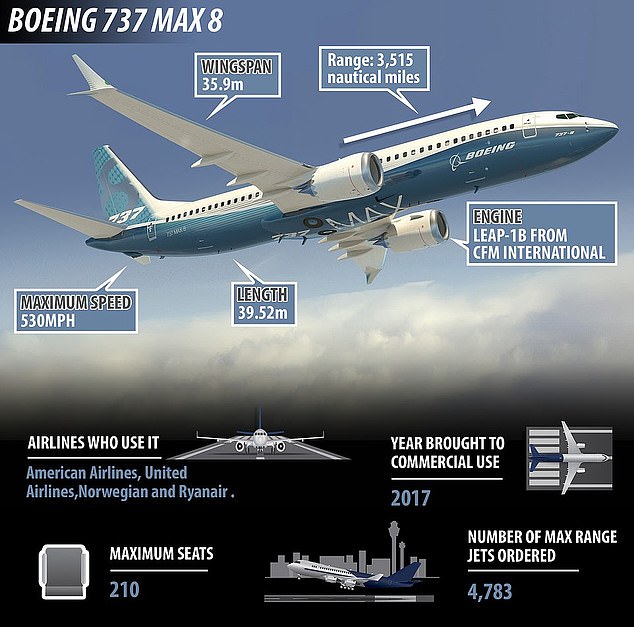

The improper design and certification of the Boeing 737 Max 8 aircraft, coupled with an overwhelmed flight crew battling a malfunctioning system they could not properly identify, led to the crash of Lion Air Flight 610 in October, according to a report by Indonesian authorities.

The report documents the investigation by Indonesia’s National Transport Safety Committee (NTSC) into the Lion Air crash that killed the 189 people on board on October 29, 2018. The Lion Air crash and the subsequent crash of Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 in March led to the worldwide grounding of the 737 Max fleet.

The crashes triggered a redesign of Boeing’s Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) software, including updates to operation manuals and crew training.

The system, designed to automatically lower the plane’s nose if it neared a stall, is suspected of forcing both Lion Air Flight 610 and Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 into the ground.

In a statement released after the report’s publication, Boeing promised its changes would prevent the conditions that led to the Lion Air crash “from ever happening again.”

The system’s redesign will correct the MCAS’s reliance on only one source of information about the plane’s angle-of-attack (AOA) sensors in flight, Boeing said, making it possible for pilots to manually override the MCAS.

“Going forward, MCAS will compare information from both AOA sensors before activating, adding a new layer of protection,” the company said. “In addition, MCAS will now only turn on if both AOA sensors agree, will only activate once in response to erroneous AOA, and will always be subject to a maximum limit that can be overridden with the control column.”

On Lion Air Flight 610, the MCAS system kept reactivating as it relied on incorrect data from a single AOA sensor, eventually overpowering the flight crew and forcing the aircraft into the water, according to the NTSC’s report.

A preliminary report by Ethiopian government officials also found that the two AOA sensors had different readings and the plane’s computer system pushed the nose down four times into a steep 40-degree dive as pilots struggled in vain to regain control.

Pilots struggled to coordinate actions

During the 11-minute flight on the Boeing 737 Max 8 from Jakarta to Pangkal Pinang, the captain and first officer struggled to coordinate with each other as the emergency grew more severe, investigators found. As the MCAS system forced the nose down more than 20 times during the flight, the first officer failed to remember checklists he should have had memorized, the report stated, then struggled to locate emergency checklists in the flight manual.

In conversations captured on the cockpit voice recorder before the flight took off, the captain told the first officer he was suffering from the flu. The first officer said he had been awakened at 4 a.m. for the flight, which wasn’t his routine schedule.

An Indonesian National Transportation Safety Commission official examines a turbine engine from the Lion Air flight 610 in Jakarta, Indonesia, on November 4, 2018.

The problems on board Lion Air Flight 610 began even before the aircraft left the runway, as the captain’s stick shaker — an emergency system designed to warn the pilot of an imminent stall — suddenly activated. It remained active for most of the flight. Within 15 seconds, warnings appeared on the pilots’ displays, alerting them that there were disagreements between key instrument readings.

Two minutes into the flight, the MCAS system adjusted the aircraft’s trim to push the nose down. It would keep doing this until the airliner eventually crashed.

“The multiple alerts, repetitive MCAS activations, and distractions related to numerous ATC communications contributed to the flight crew difficulties to control the aircraft,” investigators concluded as part of the contributing factors to the crash.

NTSC investigators spread the blame across several different organizations and factors, including Boeing, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), the pilots, and the maintenance crews.

Blame centers on Boeing and FAA

But most of the blame was centered on Boeing and the FAA, pinpointing the design and certification of the 737 Max 8 as the primary root of the problems.

“During the design and certification of the Boeing 737 8 (MAX), assumptions were made about flight crew response to malfunctions which, even though consistent with current industry guidelines, turned out to be incorrect,” investigators wrote as the first of nine contributing factors to the crash.

Investigators listed the design of the MCAS system itself as a contributing factor, because it relied on information from a single external sensor, “making it vulnerable to erroneous input from that sensor.”

Investigators found that Boeing was able to design and test its own system without proper oversight or a thorough safety assessment from the FAA. Boeing engineers never expected the MCAS system to fail continuously and repeatedly, the report stated, and failed to seriously consider that possibility.

Boeing’s “discussions did not consider the failure scenario seen on the accident flight,” the report said.

In designing the system, Boeing concluded that a repeated failure of the MCAS system was no more problematic than a one-time failure, investigators found, because Boeing assumed that the pilots would simply apply the opposite trim input to counteract the MCAS.

A member of Indonesian Search and Rescue Agency inspects debris believed to be from Lion Air passenger jet that crashed off Java Island at Tanjung Priok Port in Jakarta, Indonesia Monday, Oct. 29, 2018.

But in engineering tests after the Lion Air crash, investigators found that after only two full activations of the MCAS system, the control column force was “too heavy” if the pilot didn’t quickly counteract the MCAS with trim.

Boeing assumed pilots would immediately recognize the problem and override the system with manual flight controls, and that doing so would “not require exceptional piloting skill or strength,” the report stated. Near the end of the Lion Air flight, the first officer pulled back on the control column with 103 pounds of force, but he was unable to keep the plane from diving into the ground.

Boeing had also made the MCAS system itself significantly more powerful, allowing it to push the nose down faster and further.

“Flight crew reactions were different from and did not match the guidance for the assumptions of flight crew behavior,” the report stated. Flight crews lacked key information about the MCAS system, since none was included in training of the aircraft flight manual.

“Boeing is updating crew manuals and pilot training, designed to ensure every pilot has all of the information they need to fly the 737 MAX safely,” the company said in a statement Friday morning.

Additional contributing factors focus on the development of the aircraft and its flight manuals and pilot training.

The Lion Air and Ethiopian Airlines crashes were only five months apart. The 737 Max series aircraft were grounded soon after the Ethiopian crash, as Boeing scrambled to get one of their newest airliners cleared to fly. Even now, seven months after aviation regulators around the world grounded the aircraft, Boeing has struggled to get the airliner back into service.

Indonesian investigators issued a series of safety recommendations in the wake of the crash, including six to Boeing and three to the FAA. Investigators were critical of the cozy relationship between the administration and Boeing, urging the FAA to “review their processes for determining their level of involvement… and how changes in the design [of the aircraft] are communicated to the FAA.”

“We welcome the recommendations from this report and will carefully consider these and all other recommendations as we continue our review of the proposed changes to the Boeing 737 MAX,” the FAA said in a statement following the release of the final report.

“The FAA is committed to ensuring that the lessons learned from the losses of Lion Air Flight 610 and Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 will result in an even greater level of safety globally. The FAA continues to review Boeing’s proposed changes to the 737 MAX. As we have previously promised, the aircraft will return to service only after the FAA determines it is safe.”

Lion Air failed to report prior issue with aircraft

One day before the Lion Air crash, flight crews on the same aircraft experienced the same system malfunction on a flight from Denpasar to Jakarta. With the help of a third Lion Air pilot coincidentally in the cockpit, the crew deactivated the MCAS system and flew the plane manually to its destination. But no entry was made in the maintenance log to warn later flights of the issue. The pilots on board Lion Air Flight 610 didn’t know there were any major problems on board the previous flight with the MCAS system.

“That information was not available to the maintenance crew in Jakarta nor was it available to the accident crew, making it more difficult for each to take the appropriate actions,” investigators wrote.

Following FAA guidelines, Boeing assumed the flight crew would respond immediately to deal with the MCAS problem, but investigators found that it took the crew of the previous flight on board the Lion Air 737 Max 3 minutes and 40 seconds to find a solution to the malfunctioning MCAS system, while the crew of the accident flight never found one.

“The accident was an unthinkable tragedy and one that the relatives and friends of those who were lost continue to mourn. Everyone at Lion Air sends their deepest sympathies to those who lost loved ones in the accident,” Lion Air said in a statement after the release of the final report. “It is essential to determine the root cause and contributing factors to the accident and take immediate corrective actions to ensure that an accident like this one never happens again.”

Australian aviation safety expert Geoffrey Dell, in an interview with CNN, leveled harsh criticism at both the pilots of the previous flight and the airline for this failure to record the issue.

“If a significant occurrence like that was not entered into the maintenance log, it not only says volumes about the reporting behavior of the pilots, but also brings into question the maintenance reporting culture of the airline,” Dell told CNN. “Failing to report is sometimes indicative of poor safety culture in organizations usually driven by a lack of emphasis on proper response by management at best and outright negative pressure on reporting and ‘shoot the messenger’ supervisory responses in the worst cases.”

Though the captain of the doomed flight had 6,028 flight hours and had passed all his checks, investigators found the first officer had a poor track record in training and simulations, often losing situational awareness and even struggling to control the aircraft during normal flight. The first officer’s inability to control the airplane proved critical in the closing moments of the flight.

Before the 737 Max 8 crashed, the captain kept counteracting the repeated activations of the MCAS system by trimming the nose of the plane up. In a one-minute span in the middle of the flight, the captain trimmed the nose up five separate times.

At 6:30 a.m. local time, the captain handed control of the 737 Max 8 over to the first officer for reasons that are unclear. Instead of using the electric trim buttons to counteract the MCAS system, the first officer tried to fight the system manually, pulling back on the control column with all his might.

At 6:31:46, the first officer told the captain the plane was flying down, according to the voice recorder. The pilot responded, “It’s OK.”

Lion Air Flight 610 crashed 19 seconds later.

Podhurst Orseck is pleased to announce that seven of its attorneys have been recognized in the 2020 Edition of The Best Lawyers in America by U.S. News & World Report. Our firm’s highly experienced attorneys focus their practice on litigation matters including aviation, products liability, serious personal injury, wrongful death claims, as well as complex commercial litigation, white collar defense, and more. Additionally, the firm has a strong appellate practice, handling appeals for its own attorneys and attorneys throughout the nation, in various state and federal appellate courts, including the United States Supreme Court.The following Podhurst Orseck attorneys were recognized by Best Lawyers:

Podhurst Orseck is pleased to announce that seven of its attorneys have been recognized in the 2020 Edition of The Best Lawyers in America by U.S. News & World Report. Our firm’s highly experienced attorneys focus their practice on litigation matters including aviation, products liability, serious personal injury, wrongful death claims, as well as complex commercial litigation, white collar defense, and more. Additionally, the firm has a strong appellate practice, handling appeals for its own attorneys and attorneys throughout the nation, in various state and federal appellate courts, including the United States Supreme Court.The following Podhurst Orseck attorneys were recognized by Best Lawyers:

Boeing a subi un autre revers jeudi, venu cette fois de l’Organisation mondiale du commerce (OMC) : l’Organe d’appel de l’OMC a confirmé que les États-Unis « n’ont pas retiré les subventions accordées à Boeing par les autorités fédérales, des États et les autorités locales des États-Unis et n’ont pas remédié au préjudice que ces subventions ont causé à Airbus ». L’Organe d’appel a rejeté chacun des arguments avancés par les États-Unis et il a pris en compte tous les points juridiques de l’Union européenne, selon le communiqué de cette dernière et d’Airbus. En outre, la plus haute juridiction de l’OMC a également qualifié un certain nombre d’autres programmes fédéraux et des États américains « de subventions illégales, et même de subventions prohibées, comme dans le cas du régime FSC (Foreign Sales Corporation) », ce qui représente « une victoire majeure pour l’UE ». Ce rapport demande aux États-Unis et à Boeing de « prendre d’autres mesures » en vue de la mise en conformité ; en l’absence de toute réaction de leur part, l’Union européenne aura la possibilité de demander l’adoption de contre-mesures à l’encontre des importations de produits américains.

Boeing a subi un autre revers jeudi, venu cette fois de l’Organisation mondiale du commerce (OMC) : l’Organe d’appel de l’OMC a confirmé que les États-Unis « n’ont pas retiré les subventions accordées à Boeing par les autorités fédérales, des États et les autorités locales des États-Unis et n’ont pas remédié au préjudice que ces subventions ont causé à Airbus ». L’Organe d’appel a rejeté chacun des arguments avancés par les États-Unis et il a pris en compte tous les points juridiques de l’Union européenne, selon le communiqué de cette dernière et d’Airbus. En outre, la plus haute juridiction de l’OMC a également qualifié un certain nombre d’autres programmes fédéraux et des États américains « de subventions illégales, et même de subventions prohibées, comme dans le cas du régime FSC (Foreign Sales Corporation) », ce qui représente « une victoire majeure pour l’UE ». Ce rapport demande aux États-Unis et à Boeing de « prendre d’autres mesures » en vue de la mise en conformité ; en l’absence de toute réaction de leur part, l’Union européenne aura la possibilité de demander l’adoption de contre-mesures à l’encontre des importations de produits américains.